Relevant links: Shandalar (requires Bittorrent), 2012 version, Manalink

If you’ve never played Magic, starting with Shadalar might be confusing. The Duels of the Planeswalkers series has better tutorials (though Shandalar’s tutorials are wonderfully campy), just pick whatever game from that series is current.

Additionally, a couple of important notes: by default, your upkeep phase is skipped and all non-mandatory upkeeps will automatically go unpaid unless you set the game to pause during your upkeep phase. Also, the minimum deck sizes are: 30 for Apprentice difficulty, 35 for Magician, and 40 for Sorcerer and Wizard. The game will not tell you these things, you need to know them.

Magic: The Gathering is a real-world collectible card game which came out in 1993 and made a huge impact on gamers at the time. It kicked off the massive popularity of collectible card games which continues even now (was it the first CCG? it might have been the first), and made an enormous amount of money. It seemed natural that a video game adaptation would  follow, and so it did. Many adaptations in fact, but the first was simply titled “Magic: The Gathering” – the same as the physical card game. That got confusing really quickly and fans adopted their own name for the video game: “Shandalar”, named after the world in which it takes place.

follow, and so it did. Many adaptations in fact, but the first was simply titled “Magic: The Gathering” – the same as the physical card game. That got confusing really quickly and fans adopted their own name for the video game: “Shandalar”, named after the world in which it takes place.

Shandalar was released in 1997 and, it’s sad to say, is still the best video game based on Magic. It’s now more than twenty years later and there have been quite a few other efforts but they have all been either unable or unwilling to match what Microprose did back then. Some people might attribute this to the involvement of Sid Meier: though he doesn’t appear in the credits, Shandalar was the last project which he worked on at Microprose before leaving to start Firaxis. Apparently dropping multiplayer and adding the adventure game setting were both at his direction, and they were both good moves. Multiplayer was added to the game in a later expansion, but focusing on the single player allowed for card collection, that being a large portion of player motivation in CCGs, and also a more developed AI.

That said, with all due respect to Sid Meier, the fact that no further games have been able to measure up to Shandalar’s example seems less likely to be about ability than it is about will; my suspicion is that Wizards of the Coast (the company which publishes and owns the rights to Magic) simply isn’t interested in producing a video game which can stand on its own anymore. Subsequent games all seem to have one of two objectives: they serve as advertisements for the physical card game or, like so many other video game CCGs nowadays, the game is simply a storefront – a means to sell virtual cards. Both of these approaches avoid the misstep of putting players in the position of independence from Wizards and further purchasing.

So, with all of that said, does being the best Magic-based video game mean that Shandalar is any good in its own right? Well no, but it manages to be pretty good anyway, with a few caveats. The adventure portion of the game is very clearly tacked on: each city or village has exactly one NPC for you to talk to and they all draw from the same dialogue set. Outside of the towns it isn’t any more developed, you run from village to village while trying to dodge enemies and sometimes a random special location will pop up with a little bonus in the form of cards or currency or something. That’s about it.

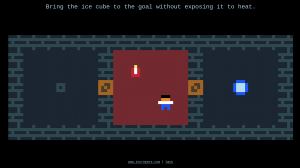

So, with all of that said, does being the best Magic-based video game mean that Shandalar is any good in its own right? Well no, but it manages to be pretty good anyway, with a few caveats. The adventure portion of the game is very clearly tacked on: each city or village has exactly one NPC for you to talk to and they all draw from the same dialogue set. Outside of the towns it isn’t any more developed, you run from village to village while trying to dodge enemies and sometimes a random special location will pop up with a little bonus in the form of cards or currency or something. That’s about it. The only other significant feature is the dungeons, which are also very simple but have some neat play modifiers and little trivia mini games to make them more interesting. That’s where you get the best cards.

The only other significant feature is the dungeons, which are also very simple but have some neat play modifiers and little trivia mini games to make them more interesting. That’s where you get the best cards.

Speaking of getting cards, this is where the game shines. With the base game and the expansions, Shandalar has a total of 649 cards for you to collect and play with. That’s a huge number, thanks to its roots in the physical game, and a good few of these are the overpowered cards which any Magic player has heard of: Moxes, Ancestral Recall, Black Lotus, etc. In other words, they’re desirable. It’s really fun to watch your card collection get more and more obscene, and your decks more and more degenerate, and the tacked-on adventure mode, with it’s simple villages and dungeons, serves as a fine medium for this. You’re not going to get drawn into the story (you’re engaged in an epic-but-uninteresting quest to save the world), but the desire to get cool stuff provides its own motivation and the fact that it takes a bit of work to get there gives you a sense of earning what you’ve gained.

The large quantity of cards gives Shandalar a good deal of replayability, as the cards that you acquire and the decks that you can make are going to be different from game to game. For a Magic veteran this can also be nice in forcing you to try different playstyles – someone who plays with lots of creatures in the physical game but who gets mostly direct damage cards in Shandalar will have to learn to adapt to the situation. (Also, you get to play with all those ante cards that no one ever uses.) However, this abundance of available cards and the randomness with which they’re acquired has it’s own drawback in that you’re unlikely to get all of the cards that you want. Building a themed deck, with many cards of a single type, is quite difficult.

The final and most important mode is the sub-game where you use your deck to play against the numerous NPCs which you encounter. It’s a faithful reproduction of Magic: The Gathering , which is no small feat given how complicated Magic can be. It’s also a reminder that translating from a physical game to a computerized one doesn’t always streamline the experience. A single turn in Magic has a lot of phases and breaks to allow for different actions, and in the physical game most of these are just skipped by mutual understanding between the players. The computer shares none of this understanding, and the way that this is implemented in Shandalar involves lots of pausing for confirmation: “Do you want to do something now? No.” “How about now? No.” “Now?” etc. There are many of these pauses, but it does allow you to set your own breaks to handle tasks at different points during the turn cycle and skip most of the rest. The remaining pauses can be quickly cycled through with a tap of the space bar. It’s more complicated than would be ideal, but it functions effectively and is probably as smooth an operation as a person could hope for. To do better you’d need to have some sort of Magic-like card game designed specifically to be played on a computer (something like… Etherlords).

, which is no small feat given how complicated Magic can be. It’s also a reminder that translating from a physical game to a computerized one doesn’t always streamline the experience. A single turn in Magic has a lot of phases and breaks to allow for different actions, and in the physical game most of these are just skipped by mutual understanding between the players. The computer shares none of this understanding, and the way that this is implemented in Shandalar involves lots of pausing for confirmation: “Do you want to do something now? No.” “How about now? No.” “Now?” etc. There are many of these pauses, but it does allow you to set your own breaks to handle tasks at different points during the turn cycle and skip most of the rest. The remaining pauses can be quickly cycled through with a tap of the space bar. It’s more complicated than would be ideal, but it functions effectively and is probably as smooth an operation as a person could hope for. To do better you’d need to have some sort of Magic-like card game designed specifically to be played on a computer (something like… Etherlords).

To contrast: the most recent game in the Duels of the Plainswalkers series (another line of games based on Magic) handles this by putting a timer on each phase of your turn. Instead of asking whether you’d like to take an action, you’re expected to pause the game whenever you’d like respond to something which your opponent has done. Inaction, or acting too slowly, is interpreted as acceptance. This simplifies things for new players, and drawing in new players is really the whole point of that series (it makes no bones about recruiting people into the physical game), and has the additional virtue of being analogous to what you’d experience if you were playing the physical game with another person – they cast a spell and you’re expected to say something if you want to counter it or make some other response. The difference being that if you’re playing the physical game you’re not sitting there watching a progress bar fill up over and over and over again as you wait for the timer to complete. Rather than quickly skipping through lots of confirmations, as in Shandalar, in Duels of the Plainswalkers you wait for lots of progress bars to fill up… It’s a pain in the butt.

So Shandalar is a faithful reproduction of another game… Is that one any good? Well this isn’t intended to be a discussion of Magic, but quickly:

Magic is the granddaddy of CCGs and isn’t quite as well implemented as a few of its successors, but it’s certainly the product of a sincere effort at crafting a quality game and it has none of the stink of being a copycat cash-in. Some of the really oddball cards don’t make it into Shandalar (Shahrazad, Chaos Orb…) thanks to the difficulty / impossibility of implementing them in a video game, but most cards from the early sets are present and function exactly as they should. If you’ve never played Magic before then you might struggle some, but if you have a basic understanding of the rules then Shadalar is a fine way to get acquainted with Magic and what it is that other people have been doing while you weren’t looking. The AI that you play against is nothing spectacular, it does some really bizarre things sometimes, but it’s perfectly serviceable. Some consideration needs to be made for just how difficult it is to make an AI for a game like this one which incorporates so very many variables – the Shandalar AI is better than average for CCGs.

So: how are you going to play this game, published back in 1997? Though you’d expect to see it somewhere like Good Old Games, it’s not available for purchase there or anywhere. Even if you managed to track down an old boxed copy you’d probably have some trouble getting it to run without issue on a modern computer. Fortunately for you, a group of fans on a CCG forum have been playing it for all this time. Mostly they’ve been maintaining it for the sake of multiplayer duels (mediated by a related but separate program called Manalink), but there is a fan-supported version of Shandalar which runs on current computers… current Windows computers anyway. I’ve made some effort getting this to work in Linux using WINE and have had no success, if someone else out there can manage that I’d love to hear about it.

Even better: a few years ago one of the developers on that forum found a way to get new cards to work with the old game – the many many Magic cards which have been added to the game through its various expansions over the more than twenty years since its initial release. This means that the playable cards in Shandalar went from 649 to almost ten thousand. … Until that effort was killed by forum drama and those patches were removed. Oh well.

None the less, the original version is still available as well as an updated version with new enemy decks and a number of other tweaks. Though the added cards were fun to play with, and I’m sorry to see that effort gone, the game arguably works better in its classic form since the AI knows how to deal with the old cards much better than with the new ones and their new abilities. Manalink still has the new cards.

I hope you’ll give Shandalar a try, it is easily one of the best collectable card games that I’ve played. And watch the tutorial videos! They are a masterpiece of camp.

follow, and so it did. Many adaptations in fact, but the first was simply titled “Magic: The Gathering” – the same as the physical card game. That got confusing really quickly and fans adopted their own name for the video game: “Shandalar”, named after the world in which it takes place.

follow, and so it did. Many adaptations in fact, but the first was simply titled “Magic: The Gathering” – the same as the physical card game. That got confusing really quickly and fans adopted their own name for the video game: “Shandalar”, named after the world in which it takes place. So, with all of that said, does being the best Magic-based video game mean that Shandalar is any good in its own right? Well no, but it manages to be pretty good anyway, with a few caveats. The adventure portion of the game is very clearly tacked on: each city or village has exactly one NPC for you to talk to and they all draw from the same dialogue set. Outside of the towns it isn’t any more developed, you run from village to village while trying to dodge enemies and sometimes a random special location will pop up with a little bonus in the form of cards or currency or something. That’s about it.

So, with all of that said, does being the best Magic-based video game mean that Shandalar is any good in its own right? Well no, but it manages to be pretty good anyway, with a few caveats. The adventure portion of the game is very clearly tacked on: each city or village has exactly one NPC for you to talk to and they all draw from the same dialogue set. Outside of the towns it isn’t any more developed, you run from village to village while trying to dodge enemies and sometimes a random special location will pop up with a little bonus in the form of cards or currency or something. That’s about it. The only other significant feature is the dungeons, which are also very simple but have some neat play modifiers and little trivia mini games to make them more interesting. That’s where you get the best cards.

The only other significant feature is the dungeons, which are also very simple but have some neat play modifiers and little trivia mini games to make them more interesting. That’s where you get the best cards. , which is no small feat given how complicated Magic can be. It’s also a reminder that translating from a physical game to a computerized one doesn’t always streamline the experience. A single turn in Magic has a lot of phases and breaks to allow for different actions, and in the physical game most of these are just skipped by mutual understanding between the players. The computer shares none of this understanding, and the way that this is implemented in Shandalar involves lots of pausing for confirmation: “Do you want to do something now? No.” “How about now? No.” “Now?” etc. There are many of these pauses, but it does allow you to set your own breaks to handle tasks at different points during the turn cycle and skip most of the rest. The remaining pauses can be quickly cycled through with a tap of the space bar. It’s more complicated than would be ideal, but it functions effectively and is probably as smooth an operation as a person could hope for. To do better you’d need to have some sort of Magic-like card game designed specifically to be played on a computer (something like… Etherlords).

, which is no small feat given how complicated Magic can be. It’s also a reminder that translating from a physical game to a computerized one doesn’t always streamline the experience. A single turn in Magic has a lot of phases and breaks to allow for different actions, and in the physical game most of these are just skipped by mutual understanding between the players. The computer shares none of this understanding, and the way that this is implemented in Shandalar involves lots of pausing for confirmation: “Do you want to do something now? No.” “How about now? No.” “Now?” etc. There are many of these pauses, but it does allow you to set your own breaks to handle tasks at different points during the turn cycle and skip most of the rest. The remaining pauses can be quickly cycled through with a tap of the space bar. It’s more complicated than would be ideal, but it functions effectively and is probably as smooth an operation as a person could hope for. To do better you’d need to have some sort of Magic-like card game designed specifically to be played on a computer (something like… Etherlords). “Survival Horror” is an odd label, given the games that it describes. Not that it’s inaccurate, there’s certainly survival and horror going on, but it was originally applied to Resident Evil, which is basically a weird puzzle game. “In order to open the next door, you must find a specific piece of music to fit into this player piano…” It’s something which I would not be surprised to see in Day of the Tentacle, and yet there it is. Just with more zombies.

“Survival Horror” is an odd label, given the games that it describes. Not that it’s inaccurate, there’s certainly survival and horror going on, but it was originally applied to Resident Evil, which is basically a weird puzzle game. “In order to open the next door, you must find a specific piece of music to fit into this player piano…” It’s something which I would not be surprised to see in Day of the Tentacle, and yet there it is. Just with more zombies. Doeo

Doeo

Control in Absorbed is responsive, as it needs to be, with a couple of caveats: You can’t shoot if there isn’t room for the projectile to appear in front of you, in other words there needs to be some space between you and your target. This will get you killed at least once. A second thing is that levels are all set up on a grid, everything is super linear, except for your projectiles – they are effected by gravity and they curve as they travel. But not very much. They almost shoot in a straight line, and just about every design element suggests that straight lines are the good and proper way for things to move, but your projectiles don’t quite do that. It’s a minor thing but it makes aiming difficult in some cases. I think it’s an interesting point how much the visual design can impact your expectation of movement.

Control in Absorbed is responsive, as it needs to be, with a couple of caveats: You can’t shoot if there isn’t room for the projectile to appear in front of you, in other words there needs to be some space between you and your target. This will get you killed at least once. A second thing is that levels are all set up on a grid, everything is super linear, except for your projectiles – they are effected by gravity and they curve as they travel. But not very much. They almost shoot in a straight line, and just about every design element suggests that straight lines are the good and proper way for things to move, but your projectiles don’t quite do that. It’s a minor thing but it makes aiming difficult in some cases. I think it’s an interesting point how much the visual design can impact your expectation of movement.